Previous

Previous

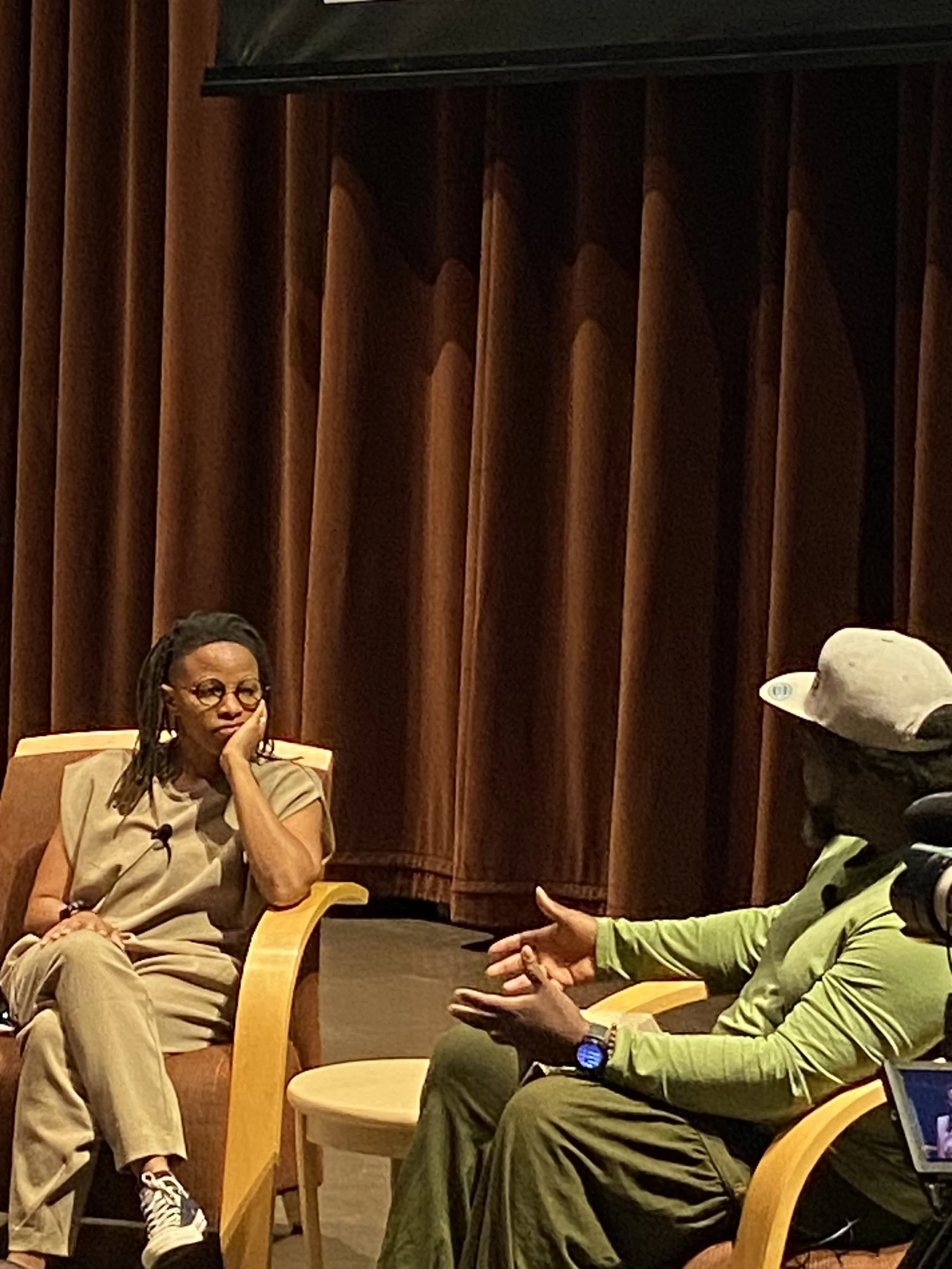

Sound Cinema: Blue Mouse Theatre

Next

Next

Raegan (she/her) is a newly established Washingtonian. She graduated from Virginia Commonwealth University where she majored in English with a minor in Professional Writing and Editing. In her spare time, she writes and reads romance novels—the smuttier the better. As a self-described serial hobbyist, she is always on the hunt for a new craft or class to dabble in. She also loves theater, music, art, and anything else where passion and creativity reign supreme. Raegan identifies as a Black, polyamorous, Queer woman and is excited to amplify voices within those communities while sharing her personal experiences.