Time may change the muse physically but will not affect the speaker’s feelings for them. The muse is eternally memorialized in the poet’s heart and within their own words regardless of the possible and potential rekindling. Although it is not clear what will happen, there is hope for their relationship to live anew.

After reading “Sonnet 100”, I wanted to reflect on my own myriads of muses. There is a symbolic relationship between a poet and a muse. Muses take many different forms and transcend more than just a mere person. They can surface from a place, an object, a memory, a personification, an identity, or anything that a poet can tap into to render a poem.

Constantly changing, what works one day may not work the next day. It is crucial for poets to say goodbye to their muses when they have served their purpose in their literary spaces.

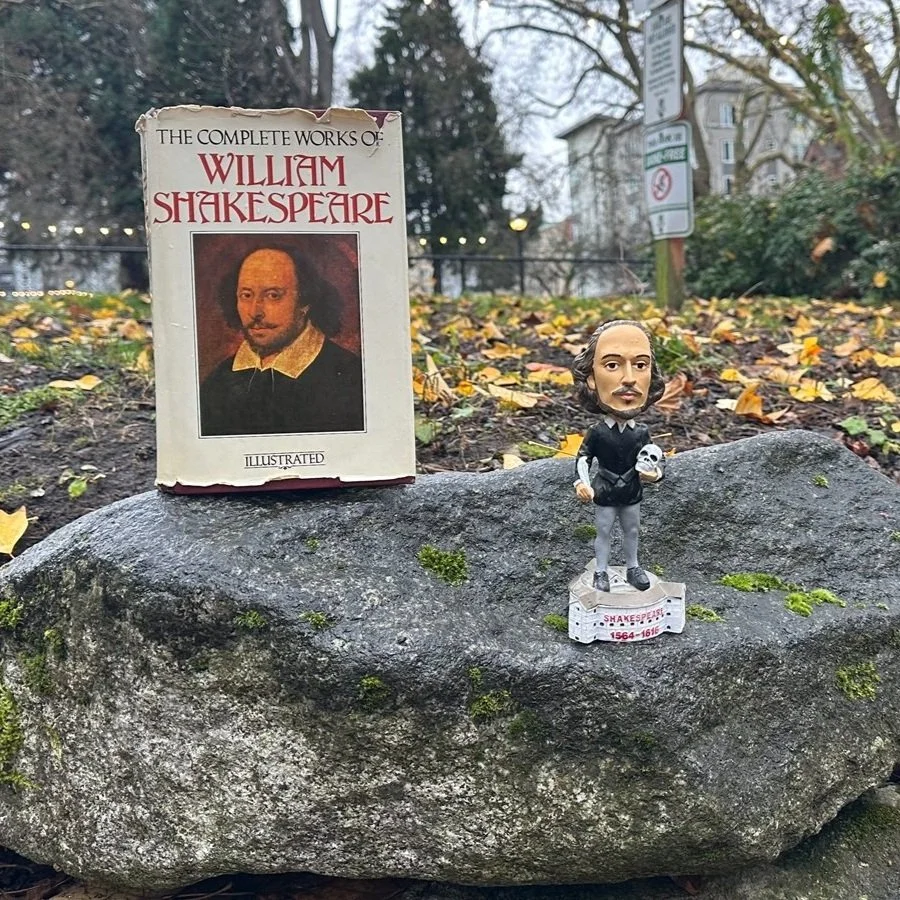

When I first dabbled in writing poetry, sonnets were my poem of choice as they were the form I was predisposed to. Every sonnet felt like a puzzle trying to get the rhyme scheme to fit my narrative. As my writing has evolved, I have learned to drift from standard forms and experiment with free verse and free form.

With poetry, most people think a poet must stick to a standard rhyme scheme interlaced with flowery language like that of Shakespeare’s to make a “good” poem. How can one place limits on something so pure and vulnerable?

At the end of the day, poetry has no rules and restrictions. Poetry is a process that asks so much and so little of the poet simultaneously. Are you willing to give yourself over?